PSA Screening: It’s A Must

Prostate cancer has no known means of prevention and no known cure for advanced-stage disease; therefore, the only method for reducing the mortality and morbidity from prostate cancer is to detect it early and treat it effectively.

Prostate cancer has no known means of prevention and no known cure for advanced-stage disease; therefore, the only method for reducing the mortality and morbidity from prostate cancer is to detect it early and treat it effectively.

Screening with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) can detect prostate cancer much earlier than it can be detected without screening.

PSA screening has been widely performed during the past decade. Now, because most tumors are detected while still confined within the gland, metastatic disease at diagnosis has all but disappeared.

Before PSA screening, it was a far different situation; most cancers had spread beyond the prostate, and treatment options were much more limited.

Although the lead-time provided by PSA screening varies, in most patients, screening provides a 5 to 10 year lead-time in cancer detection. Advances in methods for performing prostate needle biopsies and improvements in surgery and radiotherapy developed at the same time that PSA screening became widespread.

“Only method for reducing deaths from prostate cancer is to detect early and treat effectively.”

The past half decade has seen a striking reduction of prostate cancer mortality rates in the US and other countries. The decrease has been ascribed, at least in part, to early diagnosis combined with more effective treatment, although there is no proof of a causal relationship.

Nevertheless, to the extent that early detection and effective treatment do reduce prostate cancer mortality and morbidity rates, PSA screening is clearly beneficial to many patients.

Some argue that PSA screening is not beneficial for all men screened because not every prostate cancer patient benefits from early diagnosis and treatment. Some tumors might never be life threatening and rare ones are incurable by the time the PSA level becomes elevated.

However, all available evidence suggests that PSA screening largely detects cancers that have features of clinically important cancers that are destined to cause suffering and death if untreated while they are still curable.

Some also argue that PSA screening is not beneficial to men who are never affected with prostate cancer. PSA screening does provide a feeling of well being in men who have persistently normal results, and even though a normal value can be misleading, with serial screening, PSA eventually reveals the cancer.

“Metastic disease at diagnosis has all but disappeared”

Some have stated that PSA screening causes anxiety and starts the patient down a “slippery slope” fraught with risks for future side effects; therefore, PSA screening is potentially harmful. Negligible pain associated with the blood draw, and the anxiety associated with having abnormal test results goes with any medical test.

Some emphasize that PSA testing is associated with a high false-positive rate. While it is true that approximately 6% of all men screened and 60% with abnormal results have false positive tests, both patients and physicians have come to grips with these results and accept them.

Another way of explaining these figures is to say that 90% of men screened have normal results and 10% have abnormal results. If the PSA is elevated (that’s the 10% with abnormal results), there is a 40% chance the biopsy will show cancer and a 60% chance that the elevation is due to benign causes, such as enlargement.

The risks associated with the biopsy for abnormal screening results are minimal. With the advent of local anesthesia, the biopsy procedure is safe and not more unpleasant than a visit to the dentist.

Much debate has surrounded the risks associated with treatment of prostate cancer. There are risks, but this is cancer we are talking about, and with sound medical judgment, treatment selection can maximize potential benefits and minimize potential harms.

“PSA is here to stay”

Some raise concerns about economic considerations. While PSA screening, follow-up testing, and treatment have economic costs, in the long run, it is less costly to treat early prostate cancer than advanced-stage disease, and human lives are at stake in the balance.

PSA screening has been controversial since I first reported on its usefulness as a first-line screening test in 1991. Some have questioned whether PSA screening does more harm than good.

A balanced assessment of the evidence now overwhelmingly suggests that in appropriately selected men, PSA screening allows curative treatment of silent prostate cancers that otherwise would cause death and disability, and the benefits of PSA screening outweigh any potential harm.

Early detection through PSA screening is indicated for men who are at risk for prostate cancer death. Granted that until there are reliable results from valid clinical trials, it will be difficult to prove that screening is beneficial. But there is nothing new about the lack of proof in medicine. We lack formal proof from randomized clinical trials that avoiding smoking, getting regular exercise, and weight control are beneficial.

Early detection through PSA screening is indicated for men who are at risk for prostate cancer death. Granted that until there are reliable results from valid clinical trials, it will be difficult to prove that screening is beneficial. But there is nothing new about the lack of proof in medicine. We lack formal proof from randomized clinical trials that avoiding smoking, getting regular exercise, and weight control are beneficial.

The medical community has become polarized about PSA screening. Opponents take the perspective that screening should not be recommended until there is proof that it does more good than harm. Screening advocates take the perspective that with no means of prevention and no cure for advanced-stage disease, the only practical strategy for avoiding death and disability is to detect it early and treat it effectively.

This polarization is reflected in the different recommendations of medical organizations. For example, the American College of Physicians and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force do not endorse PSA screening. On the other hand, the American Cancer Society and the American Urological Association recommend that men aged 50 years and older with at least 10 years life expectancy should be offered PSA screening each year. High-risk men such as African-American men and men with a strong family history of prostate cancer should be offered screening at an earlier age.

Panels of assembled experts hotly debate the language for screening guidelines. Should screening be “performed” r should it be “offered,” or should we just say there is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation? Is it appropriate to discourage screening? Should we require full informed consent before proceeding with screening?

These seemingly subtle nuances can profoundly affect the access of men to PSA screening in clinical practice.

Physicians are generally expected to obtain informed consent for interventions that involve a risk for possible harm. The advantages and disadvantages of PSA testing should be explained to patients, but this conversation need not take the form of a formal signed consent form.

“Patients and physicians have come to grips with false-positives.”

Few of the “simple” tests in medicine require formal, informed consent. Consider cholesterol testing, breast examination, Pap smear, occult fecal blood testing, digital rectal examination, and electrocardiography.

All these tests have a potential for a “slippery slope” of follow-up testing and treatment that could conceivably be more harmful than beneficial. Nevertheless, informed consent, like apple pie and motherhood, is hard to argue against because it ensures that patients are fully aware of what they are getting into when they have a medical procedure.

On the other hand, requiring a signed consent form before PSA testing could be harmful if it discouraged PSA testing, either because it was too time consuming or it presented the issues in an unbalanced way.

An important drawback of informed consent is the time required explaining the controversy in the setting of a busy clinical practice. With most primary care physicians scheduling 15 -30 minutes per patient visit, finding the time to properly provide informed consent for a PSA test would inevitably take away from the time to discuss important health-care issues.

It would be more convenient for a physician to be able to check off a PSA test as a part of the routine laboratory testing without having to go through a formal consent process.

Moreover, if informed consent for PSA testing were to be required, it would be desirable to provide the patient with information in advance, to expedite dealing with it during the office visit.

The way in which the issues are presented to the patient is of critical importance, and it is essential for the information to be not only balanced but also appropriately weighted. We should not hide behind the absence of a prospective clinical trial.

It is important that a requirement for formal informed consent not be used as an instrument to discourage or provide an obstacle to PSA screening. All men who could benefit from PSA screening should not only be offered it but should be encouraged to have it, and men who ask for PSA screening should not be discouraged from having it, or worse, denied it.

Of course, we should explain all issues to our patients and answer their questions. It is our duty to advise our patients to the best of our knowledge, but often, we must have these conversations with incomplete information and lacking positive proofs.

PSA is here to stay doctors and patients will have their PSA screening and in appropriately selected men, PSA screening will prevent suffering and save lives.

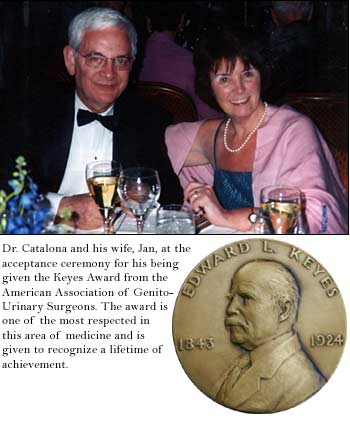

(This article is a revised version of “Editorial on Informed Consent for PSA” by William J. Catalona, M.D. from the journal UROLOGY, reprinted with permission of Elsevier Science.)